I’ll bet every one of us has said something like, “I kept telling them this was going to happen, but I guess it just fell on deaf ears.” Their ears were tuned to another stimulus.

German biologist Jakob von Uexküll defined the unique sensory environment an animal experiences as its umwelt. It is a “self-in-world” perception that enables an animal to read the signals within its environment.

All animals live within their own bespoke sensory bubbles – collectively, their umwelten – and those bubbles inform their behavior through stimuli that seem to “speak” directly to them. They understand their meaning (“This is food.” “Yikes, a predator!”), and they use that information to act (“Let’s eat,” “Run and hide!”) in ways that are rational within their worldview. Stimuli that aren’t helpful within the context of their worldview are largely ignored.

The Secret Life of Bees

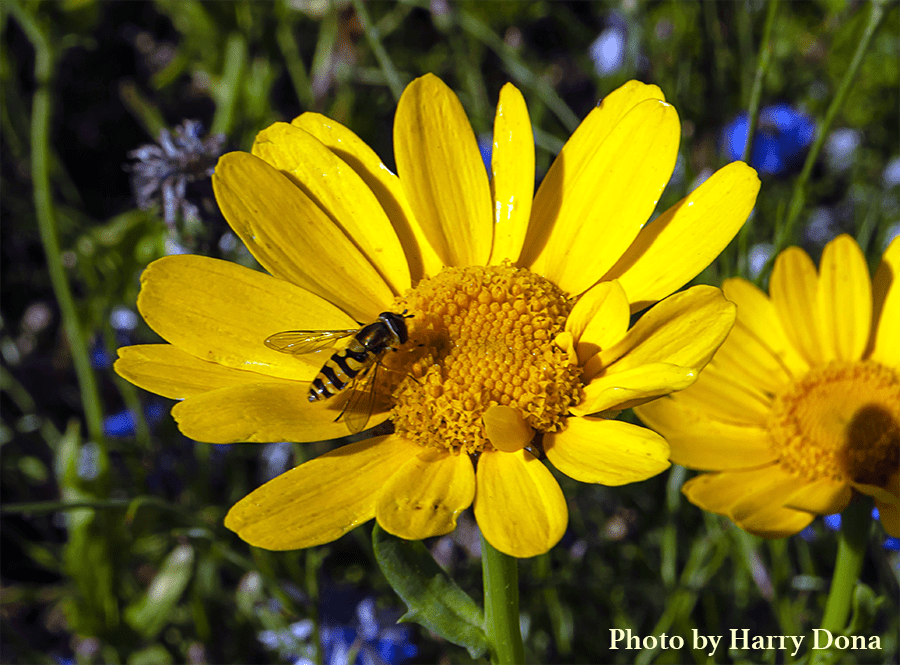

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine a honeybee flying around a garden. It sees the same beautiful, uniformly yellow flowers we see. Except they’re not uniform to the bee, who sees the ultraviolet part of the spectrum beyond our own eyes’ perception. Each flower looks like a bullseye to the bee. Every grain of pollen glows like a dazzling bright white star set against a twilight sky. The bee sees it and thinks to itself, “That’s food. I’m going in.”

Our bee doesn’t see the red cardinal sitting on a twig right next to that flower because the bee has no visual receptors for the color red. It also doesn’t see the black spider lying in wait on the flower because the spider has evolved little hairs that shine just like pollen from the bee’s perspective. We humans see both predators very clearly. They stand out starkly to us, but the bee ignores them.

We might try to warn the bee, if we could speak its “language,” but it still wouldn’t see the crouching spider, hidden redbird no matter how well or how many times we explained the situation to that bee. All it sees is pollen, bright shiny pollen. It flies right into peril.

Bespoke for Yourself

We can apply this mental framework to our antagonists, haters and naysayers who vex your efforts to steer your organization through critical moments. They don’t see the world the same way you do. They’re looking for yellow flowers – anything yellow, really – and it’s perfectly rational for them to ignore everything else, including your brilliantly written, compelling and timely messaging to them.

We at Kith have what we call the 80/20 Rule. During a crisis or critical moment, we believe your communications strategy must be focused on the 80% of people who are rational, who are willing to weigh evidence and who may be willing to give you the benefit of the doubt. The other 20% are irrational – they have their foregone conclusions (You’re company is evil.) and nothing you say or do will shake them from that path.

Well, what if I told you that the 20% were actually acting rationally. Within their umwelten, their actions and reactions are rationally based on their interpretations of the signals they receive from their world. Just as they seem irrational to me, I may seem irrational to them.

Bee the Buzz

So what can we do with our newfound appreciation for an obscure biosemiotic concept? Here are five takeaways that might make us more effective communicators:

- As communicators, we need to meet people where they are, wrapped in their bespoke sensory bubbles, and give them stimuli that speak to them.

- However, even when we try to put ourselves in their shoes, we inevitably do so carrying our own perceptions and biases. We are, after all, wrapped within our own bespoke sensory bubbles. Since we may not be able to see as the honeybee sees, we need to be careful about the assumptions we make about our audience. What we might immediately dismiss as irrational might in fact be perfectly rational behavior in their umwelten.

- So, ask them what matters. Ask them what they’re seeing, what they want to see and what they need from you. They will tell you what is significant to them and, importantly, where they’re looking for it.

- Meeting people where they are isn’t just philosophical. It’s practical. Think about our honeybee. He doesn’t fly to random places. Instead, he goes from garden to garden, flower to flower. The people you’re trying to communicate with don’t look in random places either. And, like our honeybee, their search pattern is probably just that – a pattern. If they check the company intranet once a day when they first turn on their computers and not again, then your message better be ready for them. Otherwise it’s an unopened flower, and the bee buzzes right past it.

- Finally, don’t beat yourself up when your brilliant stroke of marketing, prescient bit of wisdom or expertly crafted crisis response falls on deaf ears. Human animals seek out and respond to stimuli that support their particular worldview, and sometimes their worldview has nothing to do with your reality. Especially when they’re part of the 20% – as they say, haters gonna hate. It’s what they do. It makes sense in their world.

Continue to speak your truth to those who are listening, and, by listening, learn how to get inside their umwelten so what you have to say really speaks to them. Maybe they’ll even think it’s buzzworthy.